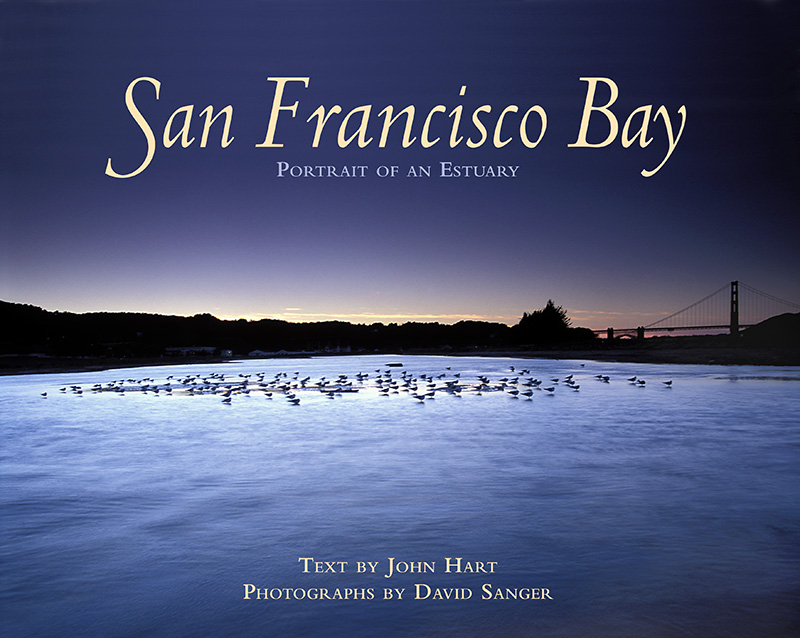

Seen from the sea and through a mariner’s eyes, the coast of California is a thousand miles of hills, a grim, gray barrier. At just one place in it is there a break, the narrowest of gaps, a doorway barely a mile wide. Approaching from the Pacific—even knowing the geography and watching for the profile of the modern bridge—you may squint into summer mist and find it no wonder that the first Europeans to explore these shores cruised right on by.

Inside that chink in the coastal armor lies the most important estuary on the western shores of the Americas; one of the world’s grandest (and trickiest) harbors; the fifth-ranking metropolitan region in the United States; and a testing ground for the proposition that eight million people and a delicate natural system can after all share a landscape and mutually thrive.

San Francisco Bay, San Pablo Bay, the Carquinez Strait, Suisun Bay, the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta: these are the parts of what scientists now prefer to call the San Francisco Estuary.

The estuary is northern California’s great meeting place, host to a mighty traffic of waters and weathers, of goods in transit and of migrant living things. Twice a day the ocean heaves in and out of the Golden Gate, and waters as far inland as Stockton responsively rise and fall. California’s largest rivers pour fresh floods into salt in a balance ever changing, ever nourishing of life. Salmon and sturgeon and bass by the kiloton move from sea to spawning waters and back again. In the autumn, nearly half the migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway settle on these shores to feed. Ships from around the world shuttle cotton and fruit and molasses, petroleum and the automobiles it will fuel, salt and cement and supercooled ammonia, and plant and animal hitchhikers that can be the most troublesome cargo of all.

The bay-delta estuary is harbor and habitat, shipyard and playground, linker and divider, fishing hole and communal cloaca. Bridges straddle it; tunnels burrow under it; airplanes bank across it, lifting from their shadows on the water top. Sailors and windsurfers lean against its winds; rowers and swimmers pull on its waters. Water diverted from its inland delta flows to much of the state’s population and irrigates half of its farms.

Estuaries are inlets where rivers reach and mix with the sea. San Francisco Bay, at about sixteen hundred square miles, is one of the grandest such minglings of fresh and salt in the United States. No mere drowned river mouth, the bay sprawls clear through several chains of coastal mountains, widening and narrowing as it works among the ranges to lap into the heart of the Great Central Valley of California, ninety miles from the sea.