Contact Marin Environmental History

We'd love to hear from you, please use this Contact form to reach us by email.

We'd love to hear from you, please use this Contact form to reach us by email.

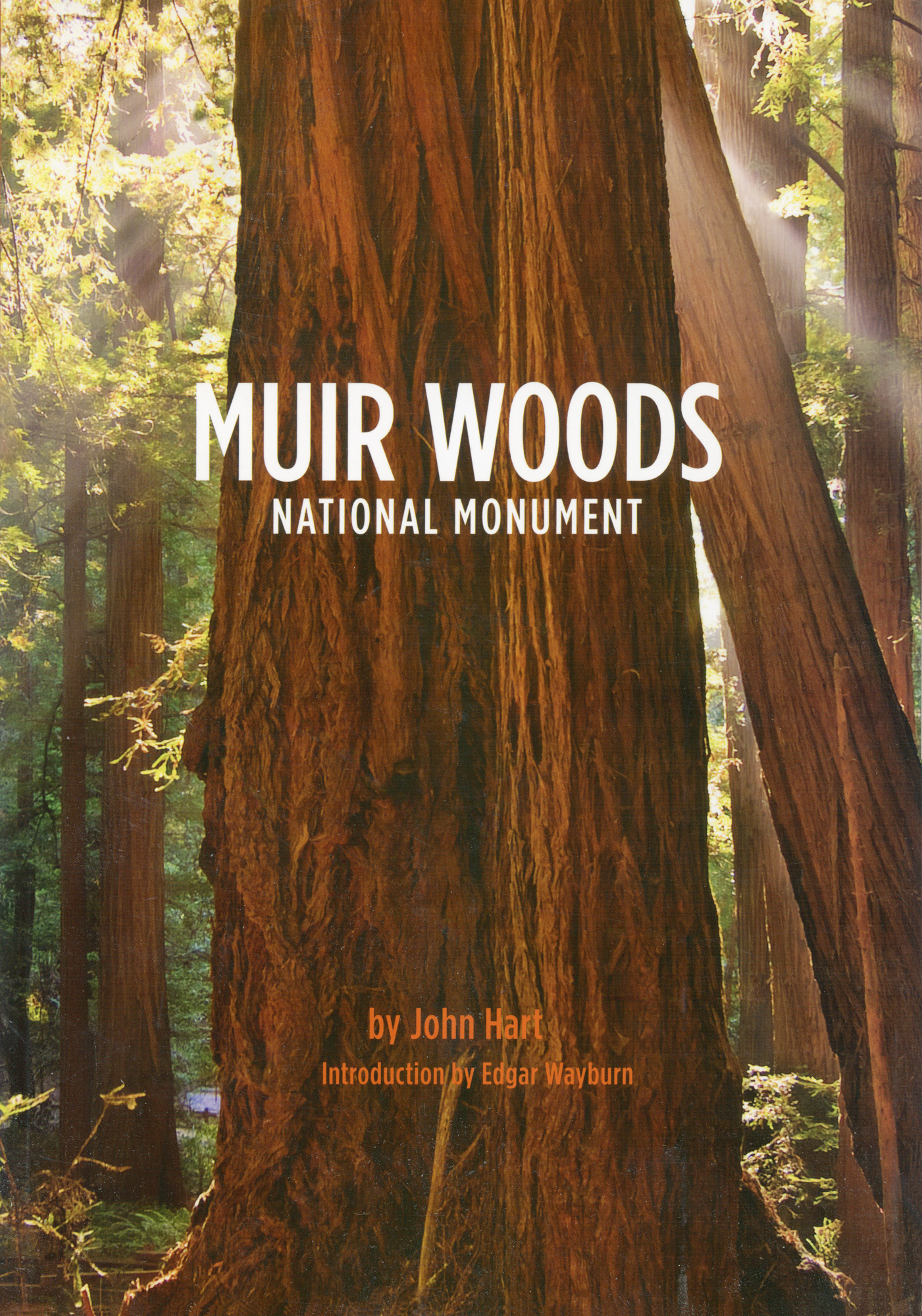

A New Book by John Hart

A New Book by John Hart

Just into Muir Woods a mounted exhibit tells time, redwood-fashion. It is a cross-section of a tree a little over a thousand years old. Until 1988, a cheerfully Anglocentric display picked out annual growth rings corresponding to the Battle of Hastings, the Magna Carta. Now we have Western Hemisphere events, from the founding of the Native American city at Mesa Verde to the arrival of Columbus and beyond, encompassed in the lifetime of one tree.

We’re meant to marvel at that thousand years, and do. But neither the Magna Carta nor Mesa Verde is anything but the very latest news—on the redwood scale of years.

Unlike the higher animals, unlike many other plants, redwoods apparently have no fixed lifespan. As they get older, their growth slows down, they produce fewer viable seeds and sprouts, but their basic functions continue unimpaired. “Immortal” is too strong a word, yet this huge fact remains: there is no built-in reason why any particular redwood tree need ever die.

A look through the plant world shows that this open-ended life is not unique. The Douglas-fir trees that grow here and there in Muir Woods National Monument, for instance, could theoretically last millennia. But very few other trees are as good as a redwood at defending themselves against natural enemies that limit potential lives. A Douglas-fir will lose a branch in a high wind; a fungus invades at the break; the end begins. A redwood with a broken limb or even a snapped-off crown is no more mortally ill than a human with a broken arm.

There are some redwood-eaters—a few species of fungus that colonize parts of the tree, a few beetles and borers that can pierce to the sapwood. But none of these do serious damage to a mature tree. Something about the wood—perhaps the particular form of tannin it contains, though the matter is poorly understood—resists invaders. Ecologist Stephen Veirs writes simply: “No killing diseases are known for established trees.”

No killing diseases. Those short-lived, two-legged, rather noisy creatures down there among the ferns and elk clover—large-brained enough to look up and wonder: smart enough, too, to know what a lifespan is—can think about that for a moment, if they choose.