Contact Marin Environmental History

We'd love to hear from you, please use this Contact form to reach us by email.

We'd love to hear from you, please use this Contact form to reach us by email.

A New Book by John Hart

A New Book by John Hart

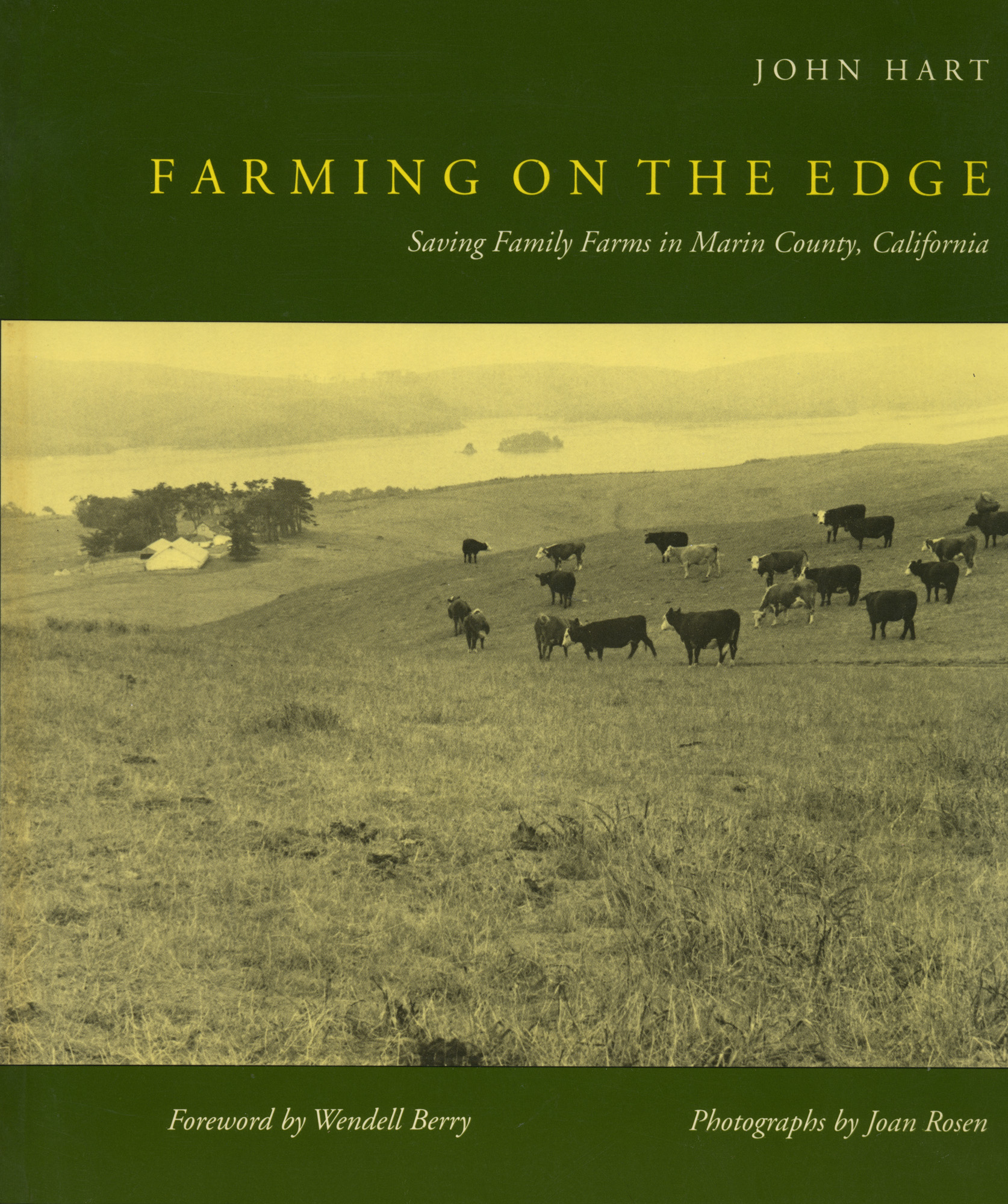

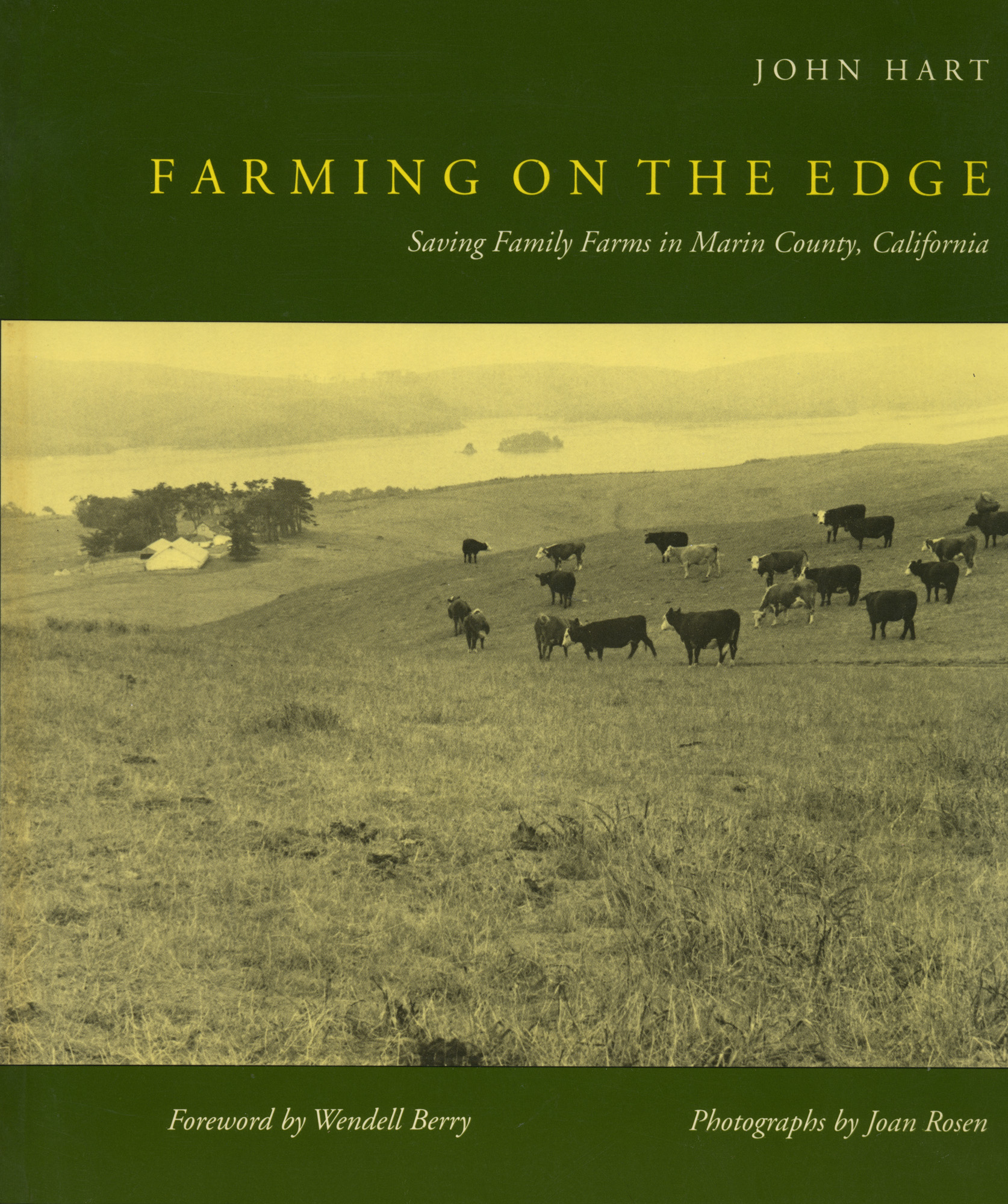

A hillside above Tomales Bay, and the California fog moves in. Not much gets in its way: a rock outcrop, a barn, a row of pale-barked eucalyptus trees. Cattle, somewhere, are lowing. The bay–as long for its width as a Norwegian fiord, a saltwater river marking the line of an earthquake fault–glimmers across to a darker, forested shore.

There was a time when government planners looked forward to 43,000 acres of suburbs on this waterside. “By 1990,” a Marin County official said in 1971, “Tomales Bay will probably look like Malibu.” That it doesn’t look like Malibu–how it came about that it doesn’t look like Malibu–is a story of much more than local interest.

It’s not some inaccessible backwater, this bay Tomales. It lies just outside a major metropolitan area, forty miles and a bridge away from San Francisco, within reach of six million people. The urban part of Marin County, across a couple of chains of hills, has the highest per capita income in the state. Even out here, the price of land per acre is well above what might be justified by the narrow profits of dairying or the erratic returns of cattle-ranching and sheep-raising–the main agricultural pursuits. Land speculators have bought and sold here; city-sized developments have been proposed.

We know in America what to expect when matters reach such a point. There may be regret; there may be protest; there may even be some ordinances passed. But once development pressure begins seriously to be felt, one thing leads to another, an avalanche of change. Sooner or later the countryside is gone, “converted” as the jargon puts it, made part of the urban scene.

Here that process was well begun. Then came a quiet revolution: something almost resembling a palace conspiracy of able planners. An election. A crucial one-vote shift on a county government board. A jerky turnabout in policy. After 1971, urban growth, in western Marin County, was officially out of favor; continued ranching was in.

But the fact that the policy shifted is not really the story. Such re-beginnings have been attempted in various places; in the typical county or town, the new rules are never really carried out, or gradually fray away as public attention fades. The remarkable thing about what Marin County did is that, in the years since 1971, it has kept on doing it: that West Marin was actually drawn back, like a piece of wood already blackening, from the urban fire.