Contact Marin Environmental History

We'd love to hear from you, please use this Contact form to reach us by email.

We'd love to hear from you, please use this Contact form to reach us by email.

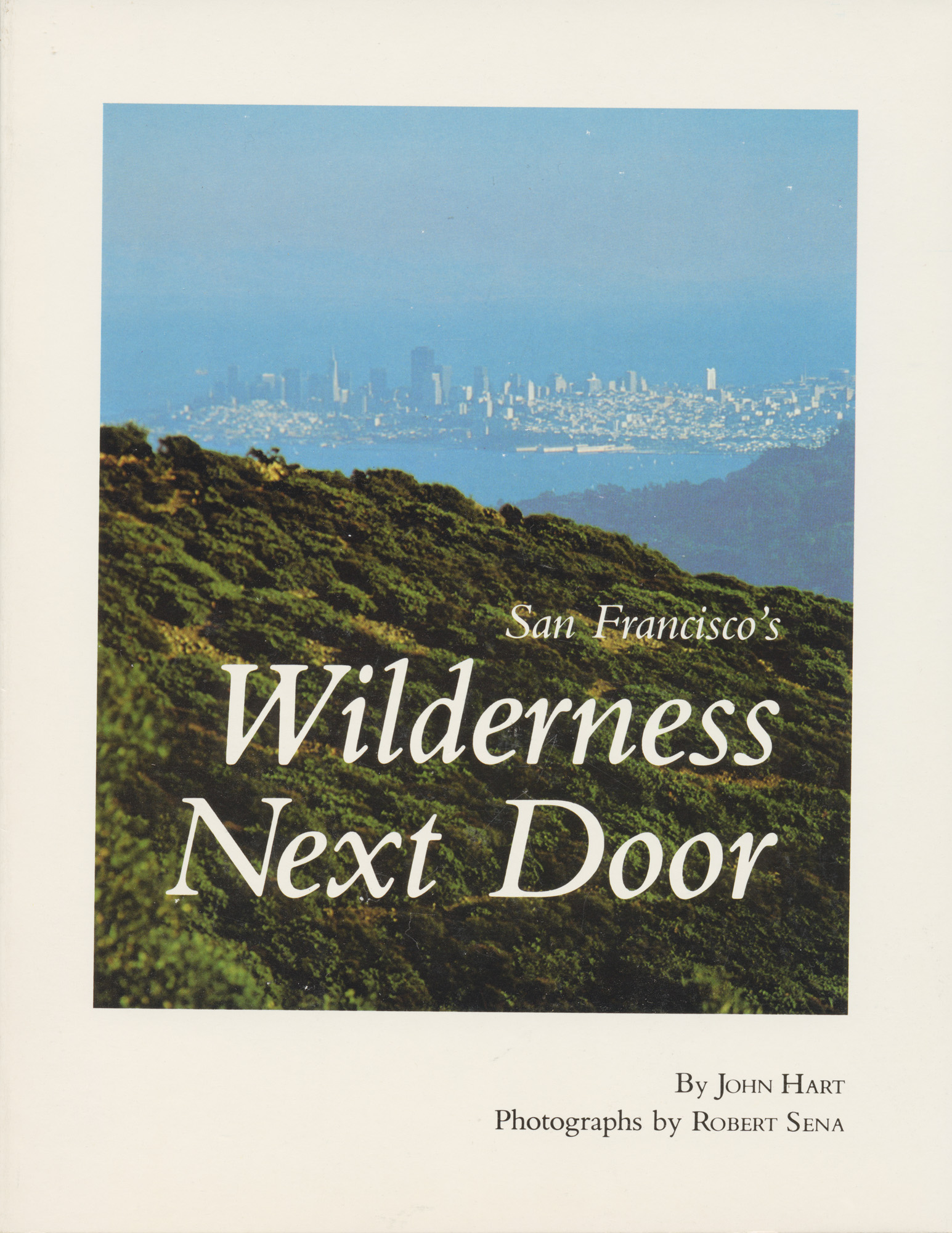

A New Book by John Hart

A New Book by John Hart

From the city of San Francisco, go north. Cross the rust-orange bridge above the wide, cold water of the Golden Gate. Travel a twisting road above the shore. Walk through a concrete tunnel in the hill: past the pit that was dug to house a gigantic coastal gun. Climb up a flight of wooden stairs—and there, from the top of the rise called Hill 129, what you have come to see is before you.

You are 900 feet above the water of the Golden Gate. Beyond, encrusting its peninsula like a deposit of white salt, is the city of San Francisco. Everything that might be dull or ugly in that city is, from this vantage, missing: rendered invisibly little: edited out. The buildings have become a texture, a stiff intricate fabric, spread over the humps and hollows. Though the mind knows better, the eye is deceived: old seamy San Francisco, urban crisis and all, looks like a trans-human city: a city without scars.

Turn now and face the north. In this direction, you find no towers, no crust of streets and houses. Instead there is country, openness, horizon. Smooth hillsides slope down to ocean-facing bowls, rise again to higher and darker ridges. On a clear winter day you can make out forty miles of field and forest and brushland, dropping cleanly to the cliffs and coves of an almost uninhabited Pacific shore, before you lose the line of the coast in the far-off headlands.

On this hill you stand on a most unusual sort of boundary. For in this place, without any intervening ring of suburban clutter, the central city gives way all at once to a hinterland almost wild. To have such a meeting of opposite landscapes at all—that is unusual enough, near any city. But to see a scene like this one, and know that what you see is permanent, that it will remain, that (in the dangerous neighborhood of an expanding urban area) it has been saved—that is nearly unheard of.

Here it has been achieved. Almost all of the land you sere from this hilltop is either densely inhabited city or public, protected parkland. The green you say is going to stay green. There is no nervous need to “see it now, before they ruin it”: fifty years from now, it will still be here. The valleys below are preserved, and so are the beaches and lagoons, and the sharp northern mountain called Tamalpais, and the far-off headlands, and more country you cannot see. And even at the south of the bridge, on the crowded urban shore, an extraordinary ring of parkland runs halfway round the twenty-mile coast of San Francisco.

Make no mistake: this is an unprecedented thing.

You might think that parks on this scale should be, even require to be, part of the makeup of any urban landscape. That a major city, a huge expanse of stone and steel and the wood of logged-off forests, should be coupled to a land-preserving park of national stature seems, on the face of it, merely in proportion. Each kind of grandeur augments the other. Standing on the windy headland over the Golden Gate, looking from the green ore tawny land across to the pale city, it is easy to fall into this way of thinking. Of course this land is a park. What else would it be?

But there seems to be a social law which causes the great city to destroy what is most interesting about its landscape. The bank of the river becomes a zone of blight. The lakeshore is divided between industry and the houses of the very rich. The magnificent view is shut out by the apartment block. Even the small town, admired for its charming location among orchards, is driven to pave and consume its own valuable setting.

And so we have built cities in which the feeling of being in any definable place whatsoever is lost: not single towns but endless agglomerations of towns, spreading across whole counties and threatening to dominate the landscapes of whole states.

The growing city-mass seldom leaves much green land within its huge perimeter. The urban planners of the nineteenth century set aside Central Park and Golden Gate Park; their successors in today’s vaster metropolises are doing less well. Away from the city—a long way away—the nation has preserved splendid park and forest lands; but these in most cases are distant even from the suburbs and are almost useless to people who live in core cities and own no cars.

Our world has pulled apart into unsatisfactory halves: the urban expanses-which people may claim to dislike, but where, willy-nilly, they work and live-and the far-off wilderness and recreational lands, reachable only at large expense in money and in time.

It should not be so. It approaches insanity that it should be so.

In many places, in many ways, people are trying to prevent it from being so: trying, at least, to rescue fragments of urban parks and greenbelts that might have been.

But if there is one place where success in that effort can be called major, it is here, at San Francisco. Around the Golden Gate a park has been built that would be magnificent anywhere, but whose existence, so near to the great city seems scarcely credible: a wilderness next door.

Notifications